- (Re-)introducing simp

- Simple AST

- Amortizing allocations

- Pointer compression

- Bump allocation

- Super flat

- Fin

In my previous post, I introduced the simple programming language. Near the end of that post, I mentioned that the parser isn't very efficient.

Let's try to optimize it!

If you're just curious about the title of the article, you can skip ahead to that section.

(Re-)introducing simp

First, a quick recap on the programming language being implemented here:

fn fibonacci(n) {

if n < 2 { n }

else { fib(n-1) + fib(n-2) }

}

let result = fibonacci(30);

It's a very simple, language consisting of:

- Variables

- Functions

- Various kinds of expressions

- Conditionals

It's not particularly useful, but it has enough stuff to be a good testing ground for experimenting with parsers.

Simple AST

Currently, the implementation uses a recursive descent parser which produces an abstract syntax tree (AST). The AST represents code in a more structured form, which is easier to work with in subsequent compilation passes.

Here is a small subset of the full AST definition:

enum Stmt {

Expr(Box<Expr>),

// ... other statements

}

enum Expr {

Block(Box<ExprBlock>),

// ... more expressions

}

struct ExprBlock {

body: Vec<Stmt>,

}

It highlights a few things:

- Each kind of

StmtandExpris in aBox, to allow these types to be recursive. - Sequences are stored in

Vecs.

This kind of design is simple and flexible. Unfortunately, it also uses a lot of memory, and each syntax node requires many separate allocations.

A note on benchmarking

Benchmarking is difficult. It's very easy to introduce bias or measure the wrong thing.

We'll be relying on two metrics:

- Throughput in lines of code per second

- Maximum memory usage

The scenario will be to parse a set of files with different sizes, starting at a few kB and going up to 100 MB. We're effectively measuring how much time it takes to construct the AST, and how much memory it uses. We won't be measuring anything beyond that.

A 100 MB file has nearly 10 million lines of code! The reason we go that high is to prevent the CPU from storing the entire file and its AST in CPU cache.

Don't over-interpret these numbers! All they'll tell you is the relative performance of different kinds of tree representations.

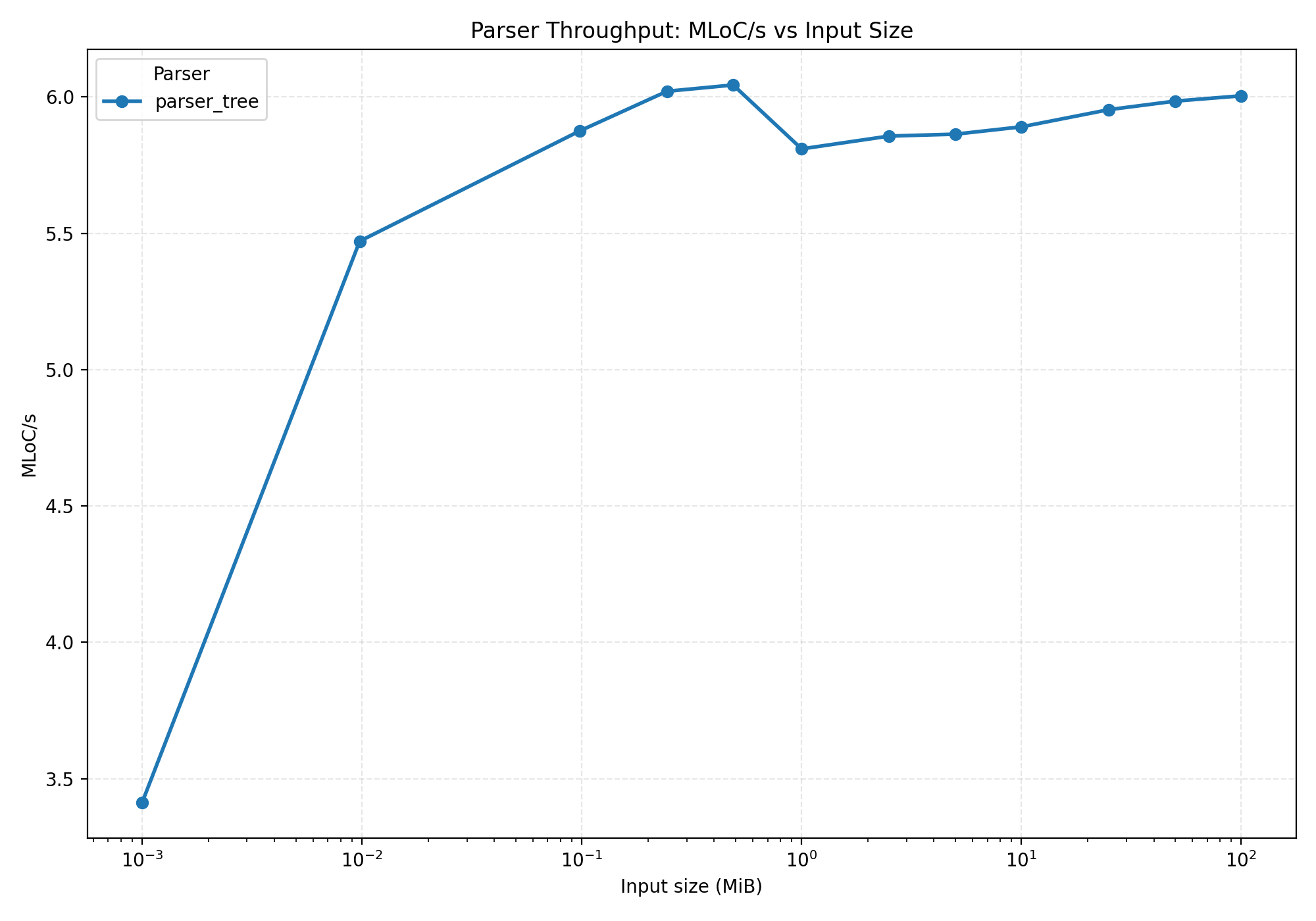

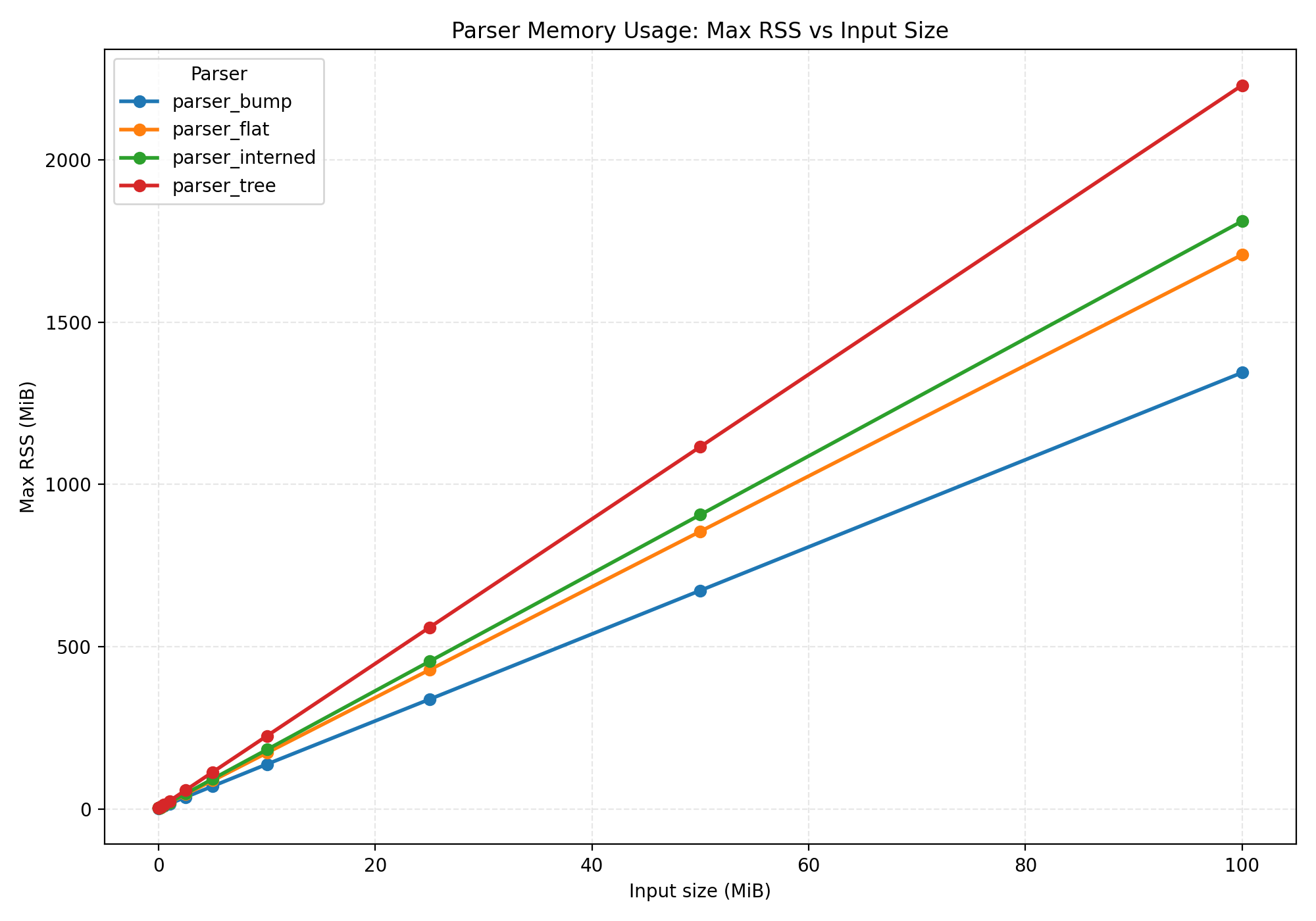

Simple tree AST results

- The Y axis is in millions of lines of code per second.

- The X axis is

log10(input size).

We're using log10 for the X axis, otherwise all the smaller inputs would be crammed to the

left side of the plot. This way the results are more evenly spread out.

Our memory scales ~linearly with the size of the input, so no log10 here, as a straight

line tells a better story.

We have nothing to compare this to right now, so these numbers are pretty meaningless. We're clocking in at ~millions of lines of code per second, so it's not too slow... but we can do better!

Amortizing allocations

Here's StmtFn, the syntax node for function declarations:

// `fn f(a,b,c) {...}`

struct StmtFn {

// fn f(a,b,c) {...}

// ^

name: String,

// fn f(a,b,c) {...}

// ^^^^^

params: Vec<String>,

// fn f(a,b,c) {...}

// ^^^^^

body: Block,

}

Each name and parameter in the declaration turns into a separately heap-allocated string.

String interning

Instead of storing owned Strings, we'll store an index into a string buffer.

That string buffer will also keep track of where each string is in the buffer,

so that we can find equivalent strings later.

Interning is a "get or insert" operation on that string buffer. It will allow us to re-use memory for strings and identifiers which appear multiple times in the same source file.

Here's how our structure changes:

struct Ast {

identifiers: Interner<IdentId>,

}

struct StmtFn {

name: IdentId,

params: Vec<IdentId>,

body: Block,

}

We'll do the interning while parsing:

fn parse_expr_ident(c: &mut Cursor, ast: &mut Ast) -> Result<Expr> {

let token = c.must(LIT_IDENT)?;

let name = c.lexeme(token);

let id = ast.intern_ident(name);

Ok(Expr::Ident(Box::new(ExprIdent { name: id })))

}

This was a relatively painless change!

A nice property of interning all strings is that to compare them, all you need is their ID, because identical strings are guaranteed to have the same ID. You don't have to compare the actual string memory.

O(1) string comparisons, nice!

During traversal, we'll have to resolve these IDs to the actual strings if we want to print them.

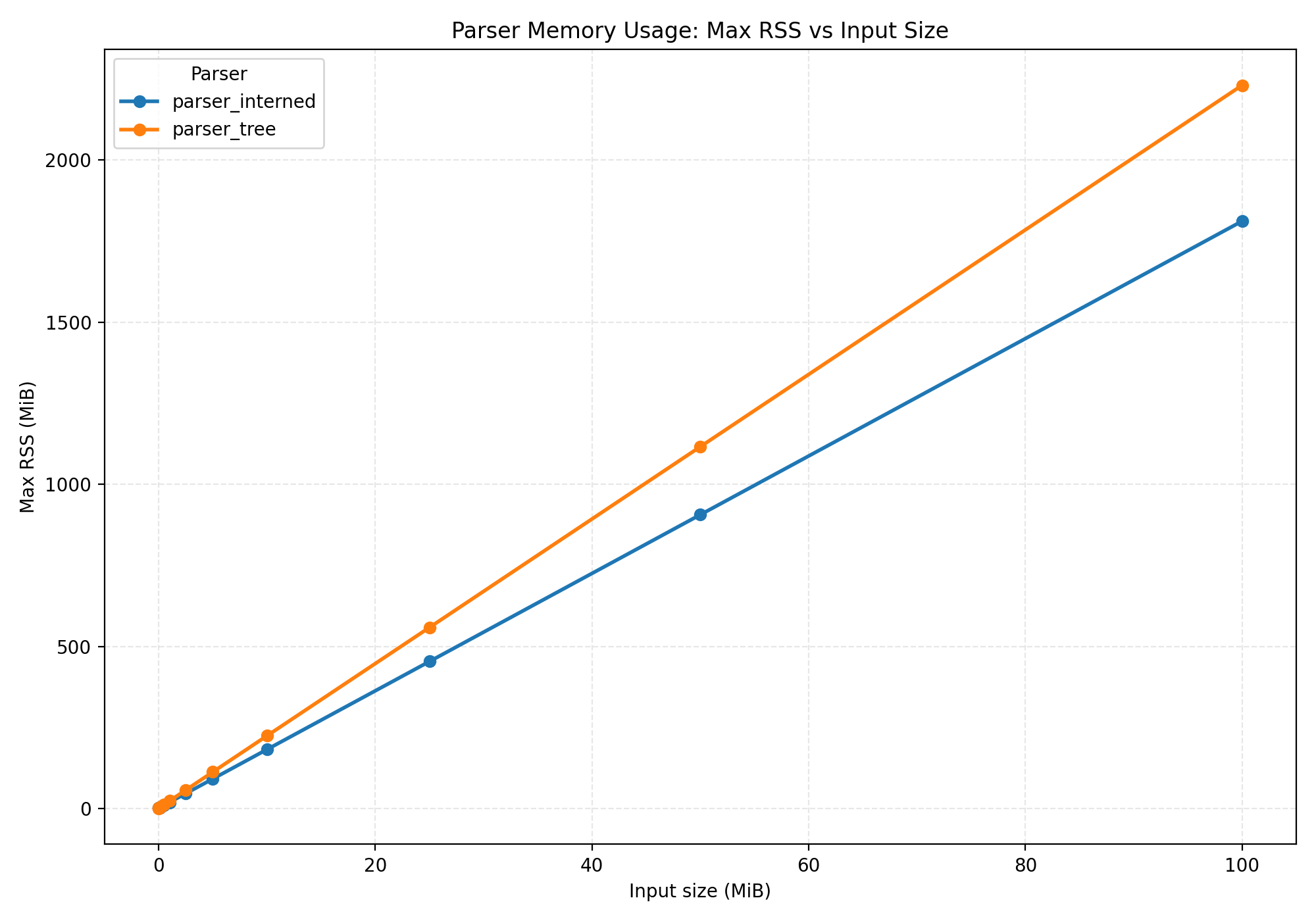

Interning results

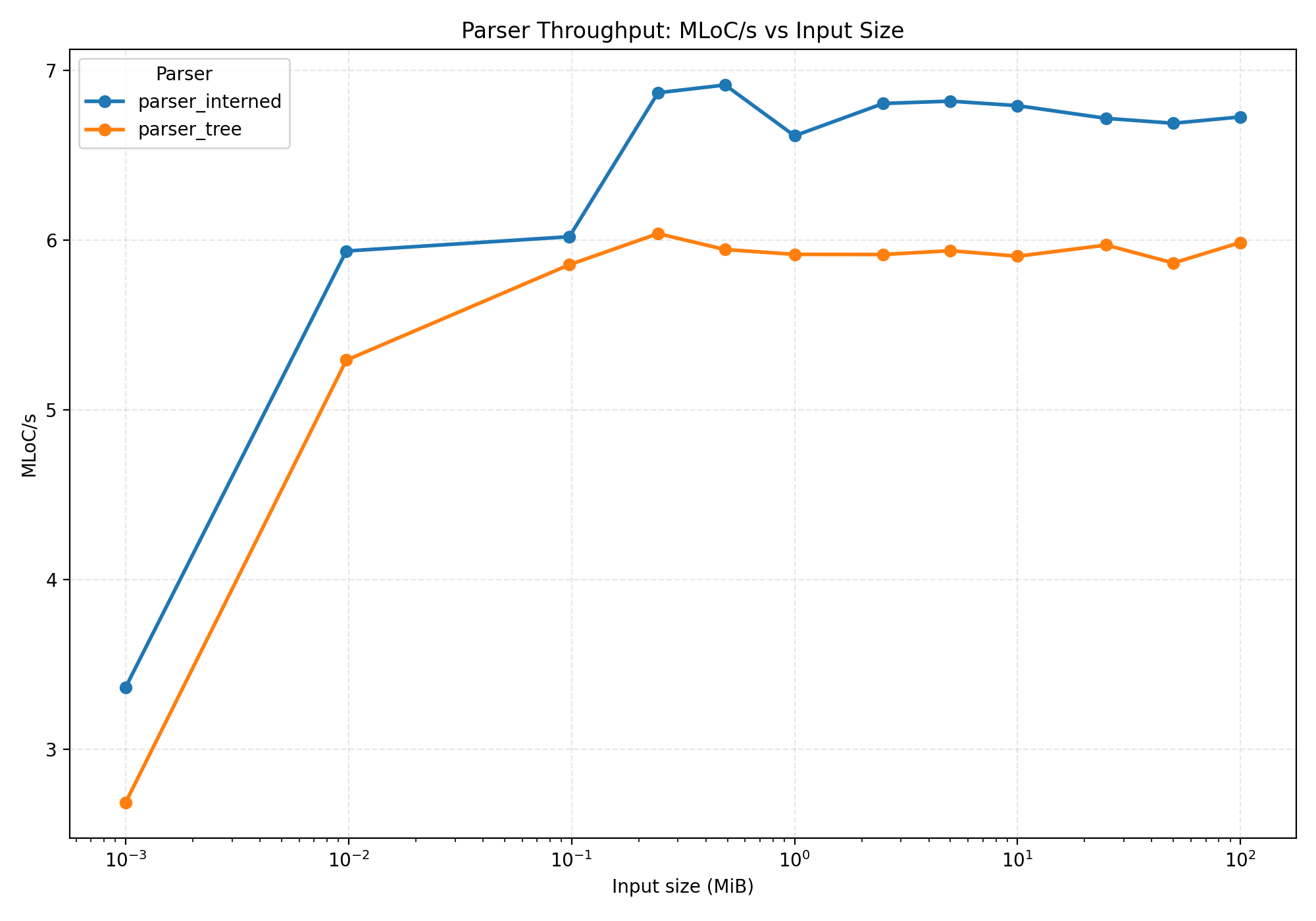

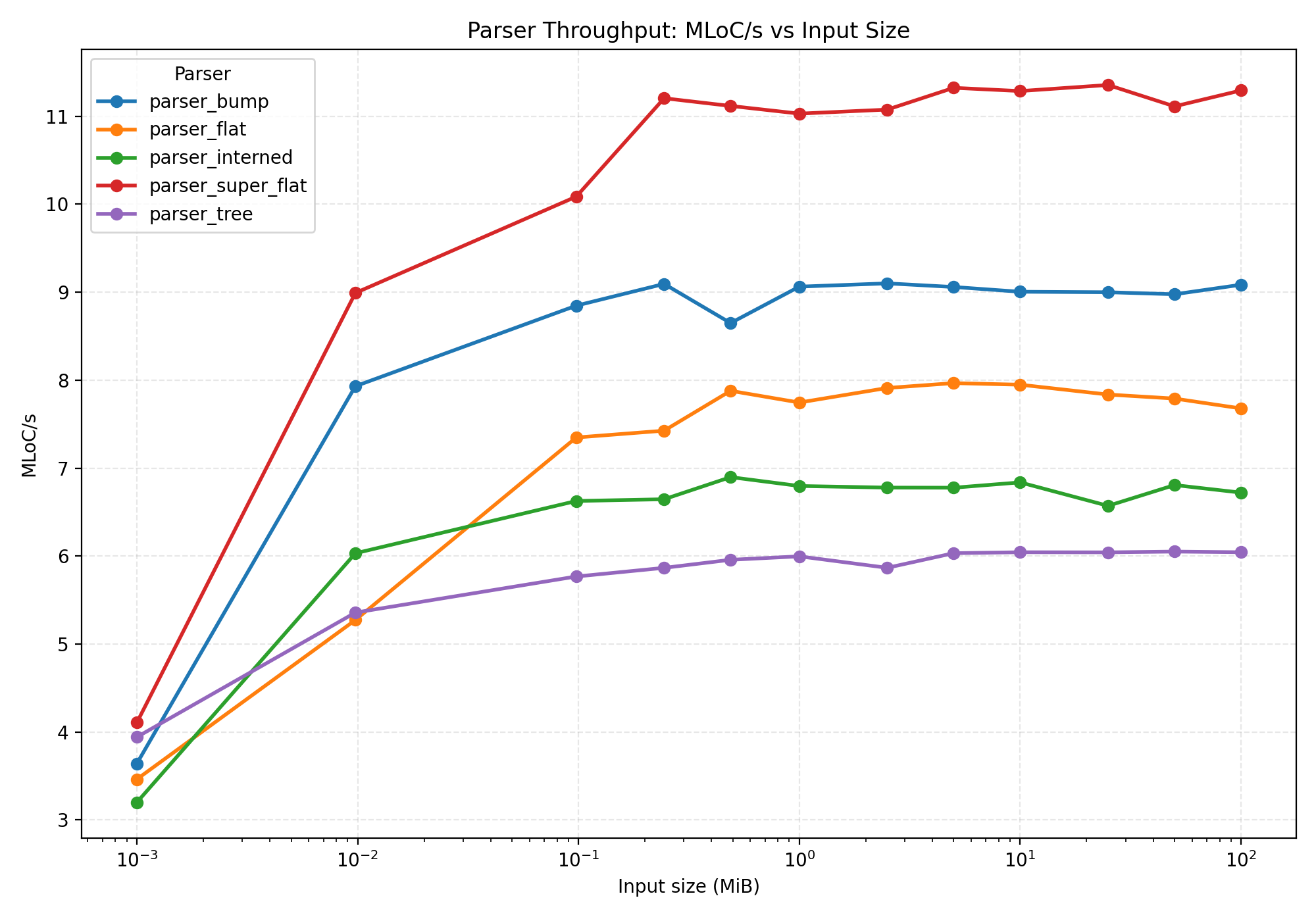

In this graph, higher is better. So interning strings is actually faster!

This is a bit counter-intuitive, though. Why does it take less time to do more work? We're now hashing each string, looking it up in a map, and then either returning an ID after optionally allocating something. Previously we were always allocating.

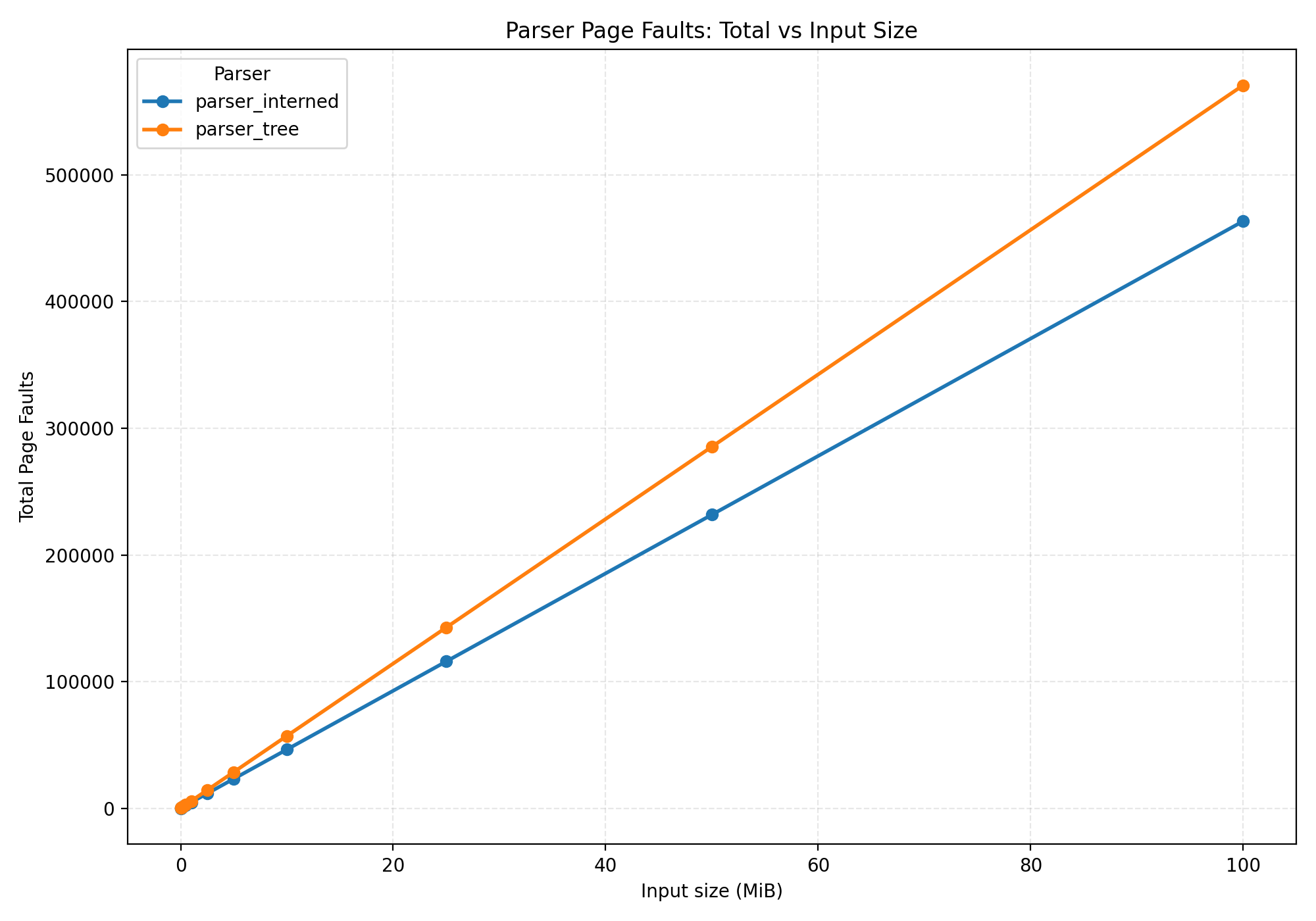

The next graph will partially answer that:

A page fault is a signal to the operating system that the process is trying to use a page it has allocated, and so the page must be assigned a physical address in RAM.

The more memory you use, the more page faults there are. And they add up quick! It turns out that using less memory also means the CPU has to do less work.

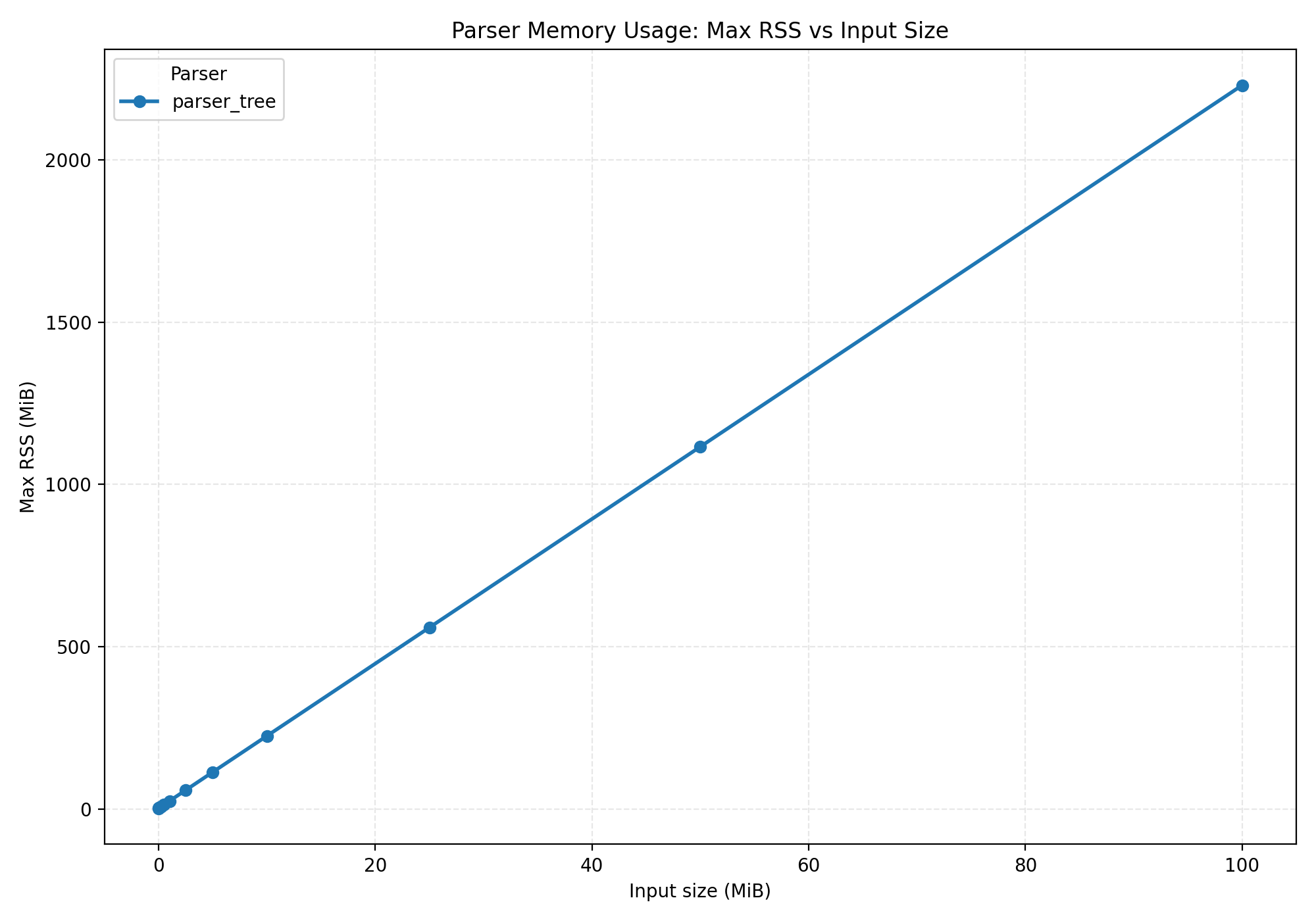

So, are we actually using less memory?

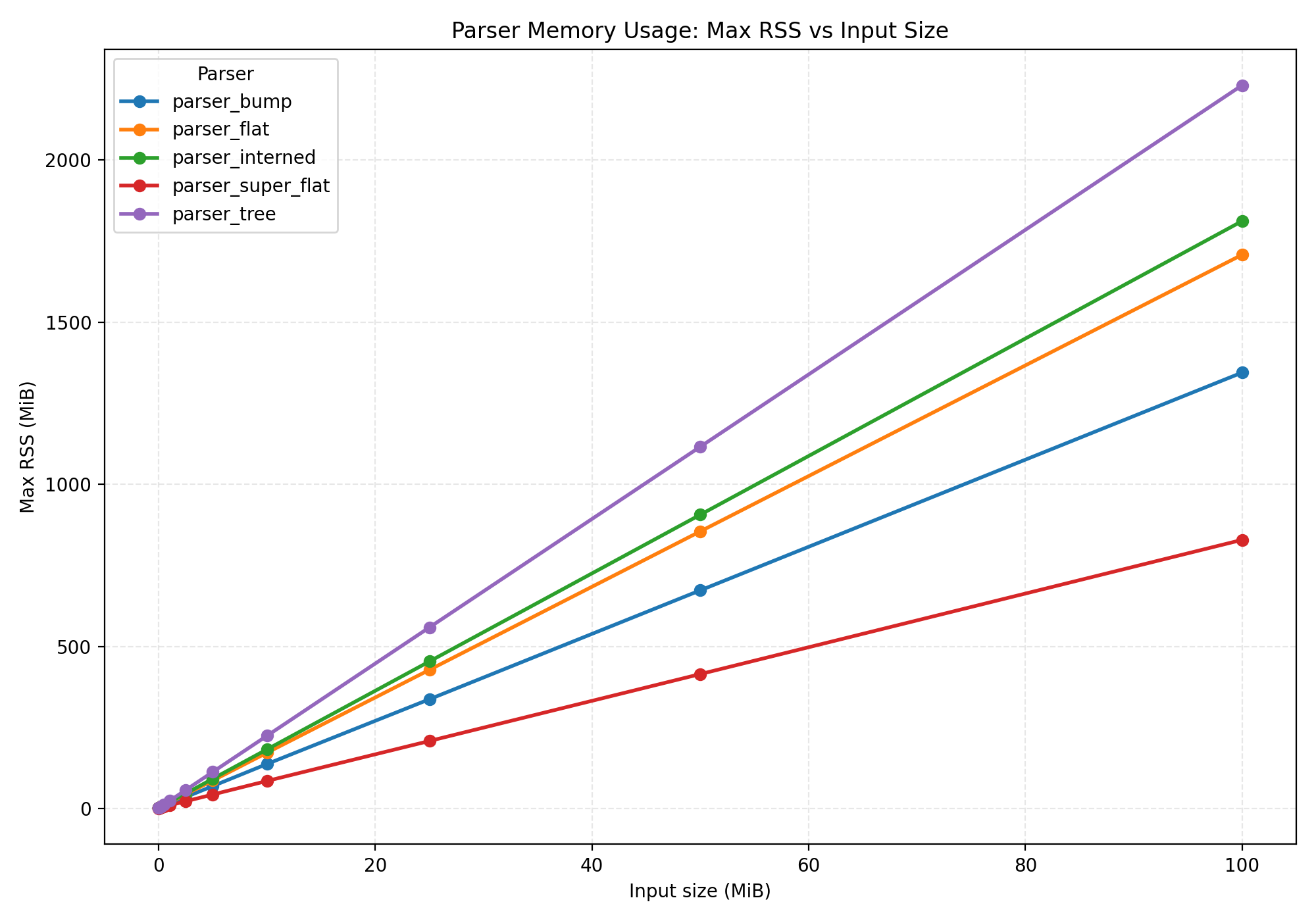

Yes, by quite a bit! We peak at ~2.3 GB for the "simple tree" representation, and at ~1.8 GB when interning strings. That's more than a 20% reduction!

Memory usage and page faults are directly correlated. If you allocate and actually fill 2 GB of memory, with a page size of 4096 bytes, we can predict ~500 thousand page faults. That's exactly what we see in the graphs above.

Allocations are expensive!

Can we reduce memory usage even further?

Pointer compression

Enter "flat AST". Here is a nice article about this concept. To summarize:

Instead of storing full 64-bit pointers, we'll store 32-bit indices. These indices are relative to the base of a memory arena.

The result is that nodes are allocated in contiguous arrays, which allow us to

amortize the cost of those allocations. Instead of doing a malloc call per node,

we'll be doing a malloc call for every N nodes.

struct StmtFn {

name: IdentId,

params: Vec<IdentId>,

body: ExprId,

}

We'll also use interning in this AST.

I thought about whether to properly separate all the different methods in this article, but ultimately decided not to. For each kind of AST, I have to copy and update the parser... That's a lot of work, and I don't believe it would change the conclusion.

Our StmtFn no longer directly stores an ExprBlock as its body, instead it

stores an ExprId. That makes the whole struct quite a bit smaller.

We'll need a place to store nodes:

struct Ast {

exprs: Vec<Expr>,

stmts: Vec<Stmt>,

strings: Interner<StrId>,

idents: Interner<IdentId>,

}

We could also just have a single array of

Node, but that would require combiningStmtandExprinto a new enum, and I wanted to avoid any extra indirection here.

While parsing, We'll ask the ast to store new nodes, instead of wrapping each one

in a Box:

fn parse_stmt_fn(c: &mut Cursor, ast: &mut Ast) -> Result<StmtId> {

assert!(c.eat(KW_FN));

let name = parse_ident(c, ast)?;

let params = parse_param_list(c, ast)?;

let body = parse_expr_block(c, ast)?;

Ok(ast.alloc_stmt(Stmt::Fn(StmtFn { name, params, body })))

}

The ast gives us a node ID in return. We can store that node ID inside other nodes.

We're not interning these nodes. Even if you have two identical syntax trees, they'll be duplicated in the final AST.

This is pretty close to what rustc does! Is it any good?

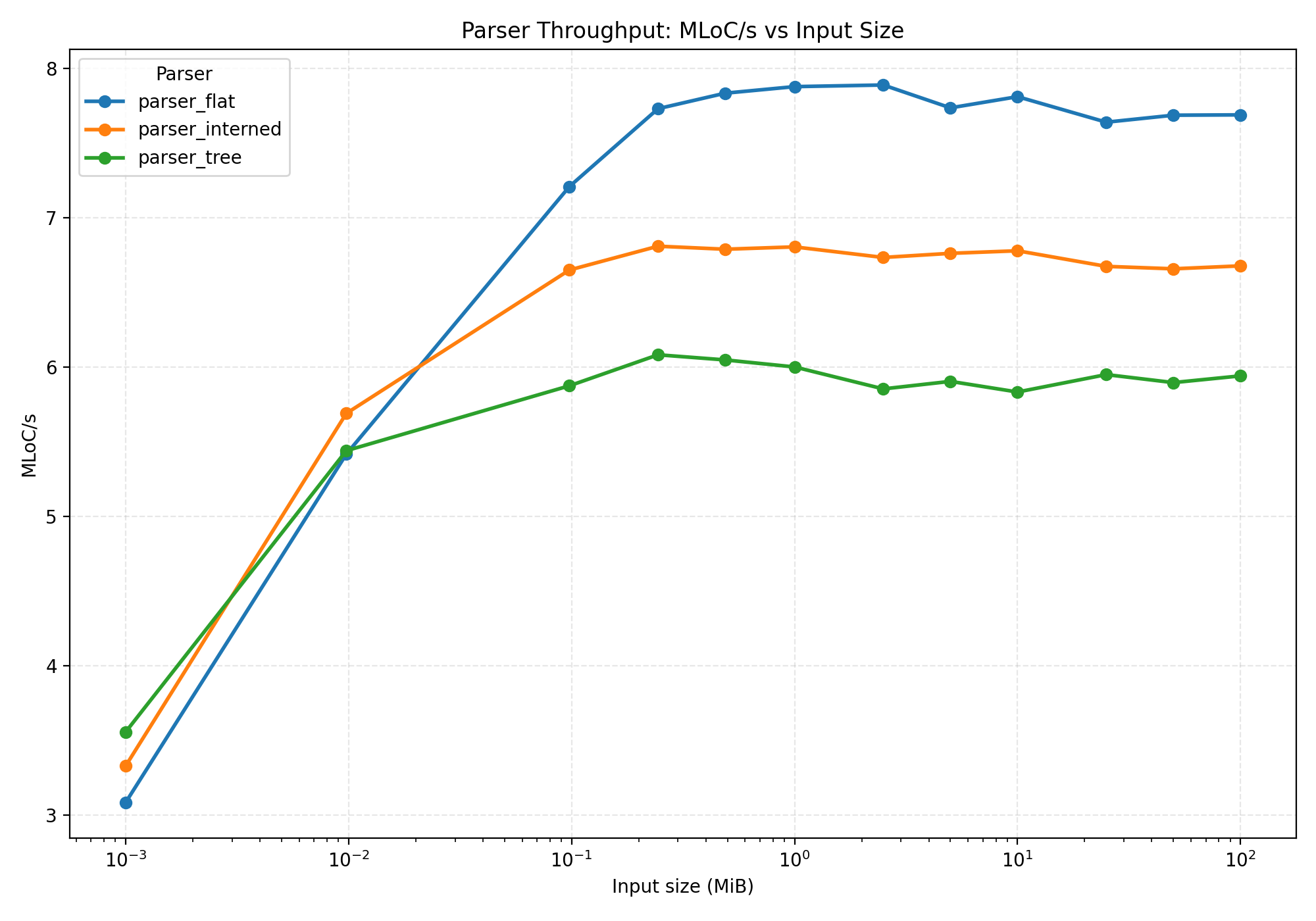

Flat AST results

Yeah, that is an improvement!

The results are a bit noisy on smaller files. At those scales, the overhead of whatever

setup the flat AST has to do is higher than the actual parsing. My computer is also

a bit noisy while running these benchmarks.

We've reduced the memory usage again! But not by a whole lot.

The reason is that each variant of the Stmt and Expr enum is unboxed. rustc

actually boxes the larger variants, which would reduce memory usage.

I didn't do that because it makes the benchmark slower, and it'd negate the whole

point of demonstrating usage of a memory arena.

Still, nice speedup!

...can we do better?

Bump allocation

A memory arena is a contiguous section of the heap. But the heap is already flat. Why do we have to flatten it further?

Well, sort of flat. Memory pages used by a process don't actually have to be contiguous. They could be anywhere in physical memory.

Let's bring in a library: bumpalo implements a bump allocator, which can be used to allocate arbitrary types in a contiguous memory arena. It provides us with address stability, as it never reallocates an existing block of memory, instead allocating a new block (twice the size of the previous one) when it runs out of space.

Our AST will go back to looking like it did initially, a tree of pointers. But this time, the nodes are bump-allocated, amortizing the cost of allocation in much the same way as the flat AST representation.

We're in Rust, with compiler-checked lifetimes. Each call to Bump::alloc will yield a reference

to the allocated value. That reference has a lifetime tied to the lifetime of the Bump allocator

it came from. So we'll have to annotate each syntax node with a lifetime in order to be able to

store them:

enum Stmt<'a> {

Fn(&'a StmtFn<'a>),

Let(&'a StmtLet<'a>),

Expr(&'a Expr<'a>),

}

struct StmtFn<'a> {

name: IdentId,

params: Vec<'a, IdentId>,

body: Block<'a>,

}

This lifetime is now "infectious", and every time we allocate or use our AST, we'll have to contend with it. Luckily, in most compilers, the lifetimes of intermediate data structures are quite linear: After you parse, you use the AST, then discard it.

Is it worth it?

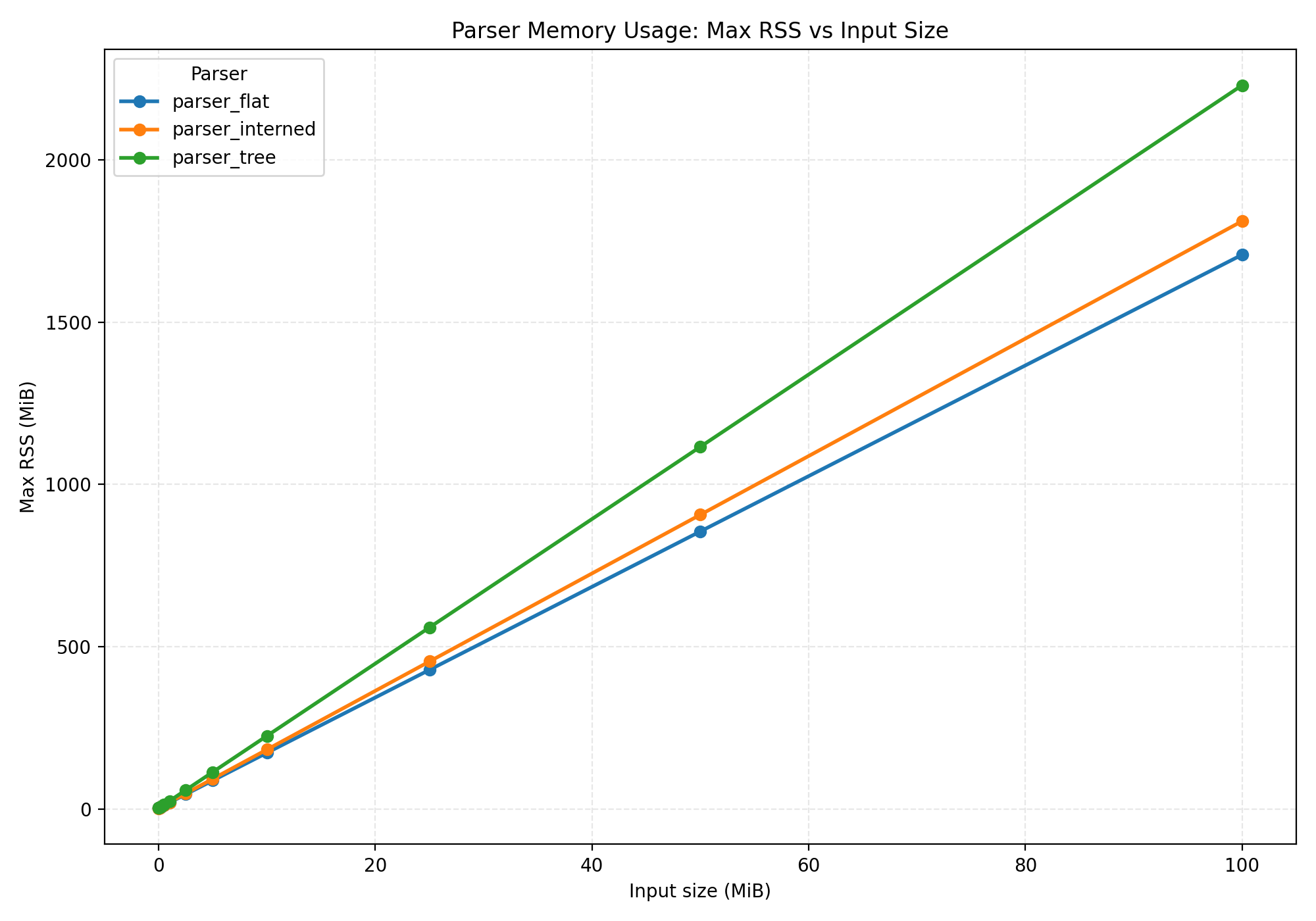

Bump allocation results

Yeah! Again, a huge improvement.

What about memory usage?

We're actually using less memory. That's because each variant of Stmt and Expr is significantly smaller.

Note that each Vec is a little bit bigger, because it now also stores a reference to the Bump allocator.

I'm convinced that just by adding string interning and bump allocation, our AST is already close to optimal, given a reasonable level of effort.

But why stop at reasonable? We can do better.

Super flat

Something bothers me about all the previous layouts. We can dictate the relative position of child nodes in memory, but we still store an index or pointer to each one separately.

For example, given a Binary expression, we need to store two pointers to the lhs and rhs child nodes.

This gets much worse if we need a dynamic number of sub-nodes. Each Vec adds 24 bytes to a

syntax node!

We can take advantage of the fact that our AST nodes fit in one of two categories:

- Nodes with a static number of child nodes

- Nodes with a dynamic number of child nodes

Going back to the example of Binary, it's in the first category, as it always has exactly two child nodes.

What if each node's child nodes were contiguous? We would only have to store the index of the first child,

and the index of second child and onward would be simply relative to the first. So for Binary:

lhsis atnodes[index+0]rhsis atnodes[index+1]

To store nodes with a dynamic number of child nodes, we'll also need to store the number of child nodes in some

kind of length field.

Each node will still have to store what its type is. For that, we'll use a tag field.

We can pack all of this information into just 8 bytes. In pseudo-Rust with arbitrarily-sized integers:

struct Node {

tag: u8,

length: u24,

first_child_index: u32

}

The length and first_child_index fields aren't always going to be used. Sometimes a node is just its

tag, like a Break expression. For fixed-arity nodes like Binary, we don't need the length.

We can re-purpose these fields to store additional information:

- The

Binaryoperator field is au8enum, so we can encode it into thelengthfield, since it's unused. - A

Stringdoesn't have any child nodes. We can store the interned string ID (au32) in the available space!

And so on. We can generalize this as fixed-arity nodes can hold a 3 byte inline value, and leaf (tag only) nodes can hold a 7 byte inline value.

I don't know if this has a name already. I've been referring to this as a super flat representation. It's inspired by flat ASTs, but goes a step further in the flattening.

Super flat implementation

This kind of representation is a lot more complex than anything we've looked at previously. We'll need

to set up some infrastructure to define these nodes, as manually indexing into a nodes array can be

quite error-prone!

We'll probably want to generate the required code. I've previously done it with offline codegen, by writing a separate program which outputs a source file containing the AST definitions.

In this case, we'll use a declarative macro:

declare_node! {

#[leaf]

struct ExprStr (value: StrId);

}

declare_node! {

#[tree]

struct ExprBinary (op: BinaryOp) {

lhs: Expr = 0,

rhs: Expr = 1,

}

}

declare_node! {

#[dyn_tree]

struct ExprBlock {

#[tail]

body: [Stmt],

}

}

The syntax here mimics Rust's struct syntax, but as you can tell, it's not quite the same.

A string expression has no child nodes, only an inline string id:

#[leaf]

struct ExprStr (value: StrId);

A binary expression has two child nodes:

#[tree]

struct ExprBinary (op: BinaryOp) {

lhs: Expr = 0,

rhs: Expr = 1,

}

Due to the limitations of declarative macros (or maybe just a skill issue on my side), we'll have to tell the macro which field belongs under which index.

Block expressions have a dynamic number of child nodes:

#[dyn_tree]

struct ExprBlock {

#[tail]

body: [Stmt],

}

The macro expands to a function which packs the node into the AST, and a few getters which retrieve child nodes.

There's also some miscellaneous runtime machinery to make it all work.

Macro expansion

Block expression:

#[repr(transparent)]

pub struct ExprBlock {

packed: Packed,

}

impl ExprBlock {

const NUM_STATIC_FIELDS: usize = 1 + 0;

pub fn pack(ast: &mut AstBuilder, tail: Opt<Expr>, body: &[Stmt]) -> Self {

let index = ast.nodes.len() as u64;

if !(index <= u32::MAX as u64) {

::core::panicking::panic("assertion failed: index <= u32::MAX as u64")

}

let index = index as u32;

let len = body.len() as u64;

if !(len <= U24_MASK) {

::core::panicking::panic("assertion failed: len <= U24_MASK")

}

let len = len as u32;

ast.nodes.push(tail.packed);

for node in body {

ast.nodes.push(node.packed);

}

Self {

packed: DynTree::new(Tag::ExprBlock as u8, index, len).packed,

}

}

pub fn tail(self, ast: &impl NodeStorage) -> Opt<Expr> {

if true {

if !Self::check_tag(self.packed.tag()) {

::core::panicking::panic(

"assertion failed: Self::check_tag(self.packed.tag())",

)

}

}

let index = self.packed.dyn_tree().child() as usize + 0;

let node = ast.get(index).unwrap();

unsafe { transmute_node(node) }

}

pub fn body(self, ast: &impl NodeStorage) -> &[Stmt] {

if true {

if !Self::check_tag(self.packed.tag()) {

::core::panicking::panic(

"assertion failed: Self::check_tag(self.packed.tag())",

)

}

}

let index = self.packed.dyn_tree().child() as usize

+ Self::NUM_STATIC_FIELDS;

let len = self.packed.dyn_tree().len() as usize;

let nodes = ast.get_slice(index..index + len).unwrap();

unsafe { transmute_node_slice(nodes) }

}

}

Binary expression:

pub struct ExprBinary {

packed: Packed,

}

impl ExprBinary {

pub fn pack(ast: &mut AstBuilder, lhs: Expr, rhs: Expr, op: BinaryOp) -> Self {

let index = ast.nodes.len() as u64;

if !(index <= u32::MAX as u64) {

::core::panicking::panic("assertion failed: index <= u32::MAX as u64")

}

let index = index as u32;

let value = op.into_u24();

if !(value <= U24_MASK as u32) {

::core::panicking::panic("assertion failed: value <= U24_MASK as u32")

}

ast.nodes.push(lhs.packed);

ast.nodes.push(rhs.packed);

Self {

packed: Tree::new(Tag::ExprBinary as u8, index, value).packed,

}

}

pub fn lhs(self, ast: &impl NodeStorage) -> Expr {

if true {

if !Self::check_tag(self.packed.tag()) {

::core::panicking::panic(

"assertion failed: Self::check_tag(self.packed.tag())",

)

}

}

let index = self.packed.tree().child() as usize + 0;

let node = ast.get(index).unwrap();

unsafe { transmute_node(node) }

}

pub fn rhs(self, ast: &impl NodeStorage) -> Expr {

if true {

if !Self::check_tag(self.packed.tag()) {

::core::panicking::panic(

"assertion failed: Self::check_tag(self.packed.tag())",

)

}

}

let index = self.packed.tree().child() as usize + 1;

let node = ast.get(index).unwrap();

unsafe { transmute_node(node) }

}

pub fn op(self) -> BinaryOp {

if true {

if !Self::check_tag(self.packed.tag()) {

::core::panicking::panic(

"assertion failed: Self::check_tag(self.packed.tag())",

)

}

}

let value = self.packed.tree().value();

<BinaryOp as Inline24>::from_u24(value)

}

}

String expression:

#[repr(transparent)]

pub struct ExprStr {

packed: Packed,

}

impl ExprStr {

pub fn pack(value: StrId) -> Self {

let value = value.into_u56();

if !(value <= U56_MASK) {

::core::panicking::panic("assertion failed: value <= U56_MASK")

}

Self {

packed: Leaf::new(Tag::ExprStr as u8, value).packed,

}

}

pub fn value(self) -> StrId {

if true {

if !Self::check_tag(self.packed.tag()) {

::core::panicking::panic(

"assertion failed: Self::check_tag(self.packed.tag())",

)

}

}

let value = self.packed.leaf().value();

<StrId as Inline56>::from_u56(value)

}

}

You may notice some unsafe code in the implementation. We're doing something that the Rust compiler can't handle for us, so we take matters into our own hands. We know that the AST is correct by construction, so we assume that a given node's child nodes exist, and they are the correct type.

This was a lot of work. How does it perform?

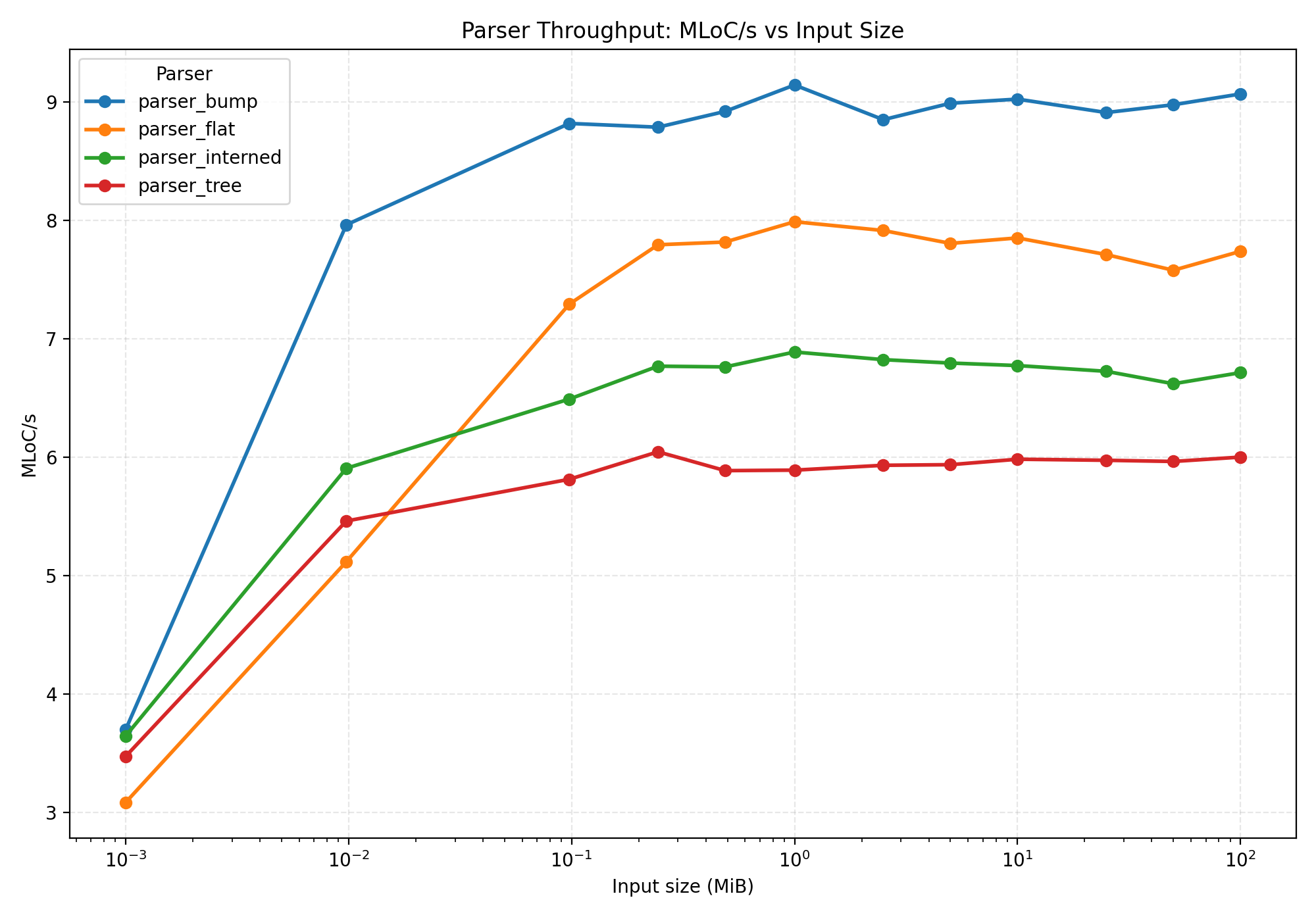

Super flat results

To me, this isn't a surprise. Look at the next graph:

A traditional tree representation uses 3x more memory than our super flat representation.

Of course, you don't usually write 100 MB large files. Luckily, it performs better at every scale.

Fin

Thanks for reading!

As always, the code is available on GitHub, this time including the benchmarks and plot generation.